History of Britain and Ireland

At least 80% of our ancestry comes from the islands of Britain and Ireland, so I've made

this entry to put the history of this part of the world into the context of our ancestors.

History is the primary basis of all my genealogical work, so there is some overlap with the

surname pages, but there's no focus here on any particular family line. I don't claim to

be an expert on any specific topic, so keep in mind that my takes might be flawed. My

object is to paint a general picture and point out events that had significance to our

ancestors. I've lumped several significant subjects into this document. Basically if it

occurred in Britain and Ireland (and I'm aware of it) it's covered, and quite a few related

subjects will come up that didn't occur in the Isles but impacted them.

The British Isles

Before the Celts

The earliest habitation of Britain by hominids (predecessors of homo-sapiens) was 900,000

years ago. Practically a million years. These were the most recent known common ancestors

between humans and Neanderthals, and went extinct also a very long time ago. The Neanderthals

arrived in Britain around 250,000 years ago. They're believed to have become extinct

about 40,000 years ago. They weren't all killed by humans. We carry their DNA even today,

somewhere in the single digits percent. It's significant, more common than several strains

of DNA that I give a lot of attention to in the documents on this site. So, there was some

production of offspring between the two species, and basically the Neanderthals were subsumed

into the human race. It wouldn't be the last time that such an absorption occurred.

Climate change will become an ever-escalating concern for the modern world. In the historical

context, the Earth has had what we call "ice ages" every 100,000 years or so. These have

occurred many times while human-like beings have been in Britain. The Isles are fairly far

to the north on the globe, so when there was more ice and lower oceans, glaciers engulfed

what would come to be called Britain. In those times it appears that humans and pre-humans

withdrew to southern europe, i.e. the Mediterranean. Even though humans have proven that

they can survive in extreme cold, glaciers are not a stable thing to be on top of. What

really determined the movement of humans was the movements

of animals. All of these early peoples were hunters and gatherers, and they followed herds

of game. But anyway, the most recent "glacial maximum" was about 12,000 years ago. The

pattern these ice ages have followed is a relatively slow cooling and increase in ice and

lowering of oceans, and then a relatively quick warming (a few thousand years) and rising of

oceans. What ultimate impact modern humans will have on this process is yet to be seen.

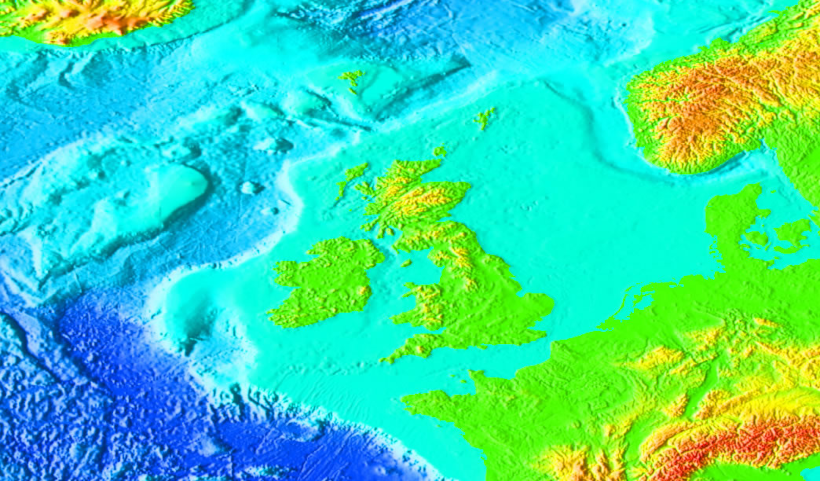

The reason why I chose the image above for the British isles is to show how relatively

shallow the water is between them and Scandinavia and mainland Europe. Up to about 9,000

years ago, when oceans were lower, there was a land path to what would become England.

12,000 years ago, as stated, it was all covered in a glacier anyway, but there was a window

of a few thousand years where there were no Islands and it was all more habitable. Waterways

haven't stopped human migration, especially not in this timeframe, but there were no barriers

even to land animals during this time. The former land between Scotland and Denmark is known

today as Doggerland, and was a place of a lot of human activity that's been uncovered by

archaeology on the floor of what's now the North sea. It wasn't fully submerged until about

6,000 years ago.

Modern humans entered Britain around the time the latter became extinct, 40,000 years ago.

This was in a window of time before the glacial maximum, and these people were evidently

then displaced to the Mediterranean as previously described. It wasn't until that time that

humans were known to have entered Ireland, 12,000 to 10,000 years ago. The geographical

position of Ireland, being farther away from the mainland, but more importantly having a

colder climate, set developments to always arrive there later, as will be seen over and over

again. So, were any of these aboriginal British humans our ancestors? It's actually

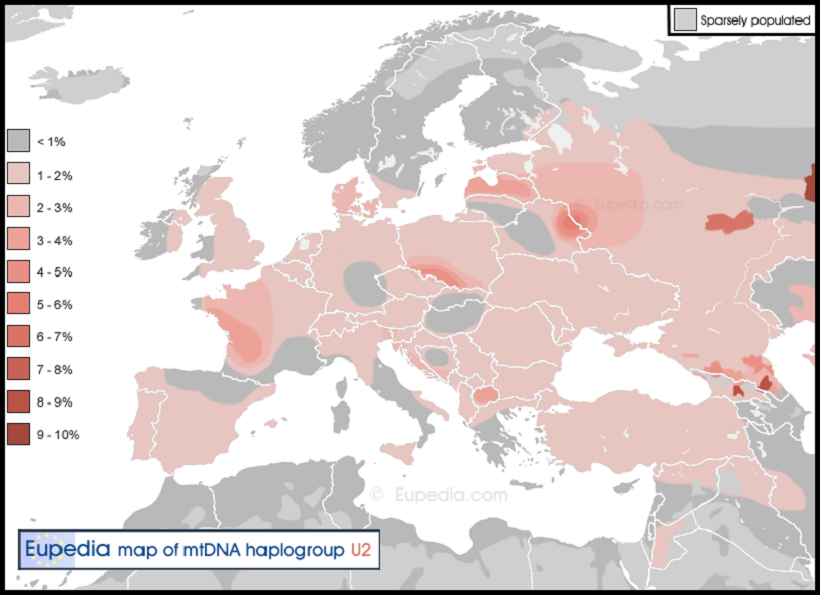

possible. The U2 mitochondrial haplogroup was definitely part of these people,

the Cro-Magnons, entering via modern Ukraine. Based on the distribution map of U2 below, it

looks like it entered Britain and Ireland specifically with the Angles and Saxons, etc

beginning in the 5th century AD. So, when the last glacial maximum ended about 12,000 years

ago, U2s and others began moving north again, and ours evidently ended up around the borders

of modern Denmark and Germany when the Roman empire crumbled. I haven't researched other

X-chromosome lines, as I don't know what any of the rest of ours were.

But what about the Y-chromosome lines? We have ancestors from both major I-haplogroups, I1

and I2. The parent haplogroup of these two is called IJ, which entered Europe about the

same time as U2. All of our I-haplogroup ancestors were with this people. Our J-haplogroup

ancestors could've been part of them too, but it's highly unlikely. Most likely they

remained in the Middle-East at least until agriculture was developed. I1 split from IJ

about 35,000 years ago. They had little impact until agriculture was adopted by a portion

in Scandinavia, about 5,000 years ago, and that's the source of the vast majority of I1s in

the world today, including our I1 ancestors. Ours migrated to Ireland and Scotland as

Vikings, and later as Angles and Saxons etc and then Normans, mostly to England. I2 emerged

about 30,000 years ago and was more prominent throughout Europe, especially in a swath from

the Balkans into modern Russia. Our I2 lines very well could'be been part of the aboriginal

people of Britain who returned when the ice began to recede about 12,000 years ago. It's

possible that I2s came to Britain with the Angles and Saxons or later the Normans, but it

doesn't follow an associated pattern like female U2 does.

There are competing theories about when the bulk of the R-M269 haplogroup arrived in Britain.

What's certain is R1a and R1b were in modern Ukraine when the ice receded. My belief is the

majority of our R1b ancestors were in Britain at least 4,000 years ago. Some theories have

them invading more than 1,000 years after that and replacing most of the people who had been

there. I tend to believe that our ancestors were much more adapters and absorbers of new

culture than sword wielding murderers who slaughtered indigenous people.

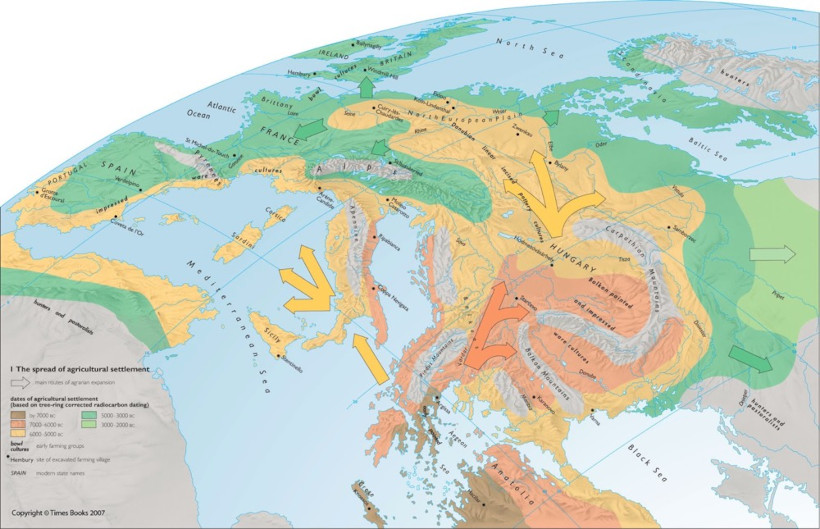

The agricultural revolution began in the Fertile Crescent also about 12,000 years ago, and

in about 4,000 years it had spread to Britain. Remember that Britain was still connected to

the mainland at that time, though water would've been no particular barrier. Farmers from

Anatolia are believed to have followed two different paths westward: along the Mediterranean

and also along rivers into what would become Germany and France. It's believed that the

olive oil diet of the Mediterranean and the butter-based one in northern Europe were

established at this time. The first known civilizations were forming in other places, but

the agricultural revolution had a transformative effect in Europe as well. In the area of

the first European empire, Greece, an agricultural economy existed from about 9,000 years

ago, yet this people bore little resemblance to what would be recognized as Greek. Similar

economies formed wherever agriculture was established.

Spread of agriculture in Europe

Prior to this, the hunter-gatherers,

some of which were probably our ancestors, resembled nomadic tribes that can still be found

in Africa today. They had a choice now to adapt to the new culture, and I expect that they

were generally reluctant. But while as farmers were settled, they also grew larger populations.

Therefore those aboriginal peoples who didn't join them would become extinct one way or

another, by conflict or by simply becoming outnumbered and subsumed like the Neanderthals

had been. While the development of agriculture was a large step in the direction toward

the way we live now, these early farmers still would've been savage to us, with practices

such as human sacrifice. They were much darker in complexion than modern Europeans as well,

even in Britain. I presume that the R1b men looked more like modern Europeans, and came in

later waves of pre-Celtic farmers.

The last subject to cover in this section is the construction of Stonehenge, though it

overlaps chronologically with the development of Celtic culture in mainland Europe. I

don't think that the nomadic aboriginal people of Britain built any kind of megalithic

structure. This was something that developed with agrarian culture, when people stopped

migrating and began to think about life in a different way. When they stayed in one place,

they began to have thoughts of ornamentation of the land. I don't know if nomadic peoples

made use of the stars or the moon. Naturally the sun was fundamental, but I suspect they

navigated more by land formations, if they weren't crossing the open sea.

It was the settled peoples who started building

things with a degree of permanence. Stonehenge of course is a famous example of megalithic

structures. But it was first built of wood, and stone construction began about 4,500 years

ago. It took about 1,000 years to complete. The builders were the first farmers in Britain.

Predominantly they came from Anatolia, and they were of the G Y-DNA haplogroup.

With them were I1s, I2s, J1s, and J2s. This is the default explanation for how our Scott

J2 Y-DNA came to Britain. If that's true, it's possible that they were involved in the

construction of Stonehenge. They were rare, and of course only a fraction of Britons were

involved. Aside from the fact that I believe they came with the Romans, the chances of

building Stonehenge are small. The same applies to our I2s. Considering the dominating

effect of Vikings and Germans on our I1s, it's highly unlikely that any of them were in

Britain this early. It seems to me that R1bs were in Britain in large numbers before

Stonehenge was completed, but I'm not aware that R1b has been found in human remains around

the site.

Stonehenge

The Celts

The term Celtic is primarily associated now with Ireland, as the Gaelic language remains

as a cultural legacy of the Celts. But Celtic actually is a very broad term, a culture

that developed in mainland western Europe and spread to Britain and Ireland. Highland

Scotland, Wales, Cornwall, and places in Europe from Spain to Turkey still show some

remnants of the Celtic language. France has its roots in Celtic culture, and it had a

lot to do with why the French language is so distinctive within European languages. The only

certain connection for us is Gaelic, Catholic Irish, which is significant but definitely a

minority in our ancestry. The other connection is genetics, the R1b Y-DNA haplogroup.

Like all western Europeans, the majority of our paternal lines were R1b. I don't believe

that all Celts were R1b, as Celtic was a culture and anyone can adopt a culture, but

certainly there's a very strong correlation between R1b and the Celts. Very likely over

95% of Celts were R1b. But since R1b is so prevalent in mainland Europe, it could've come

to Britain with the Angles and Saxons etc or even the Normans. I doubt there ever will be

a way to prove where a given R-M269 line came from, but I would guess that the majority

had been Celts and were already in Britain when the English and Normans came. English and

Norman are also cultures, and though they had strong genetic connections, I believe that

more Celts in Britain converted to new cultures than had to be killed or driven to Ireland

or something. I expect that most of our R1b ancestors were in Britain

before even Celtic culture arrived.

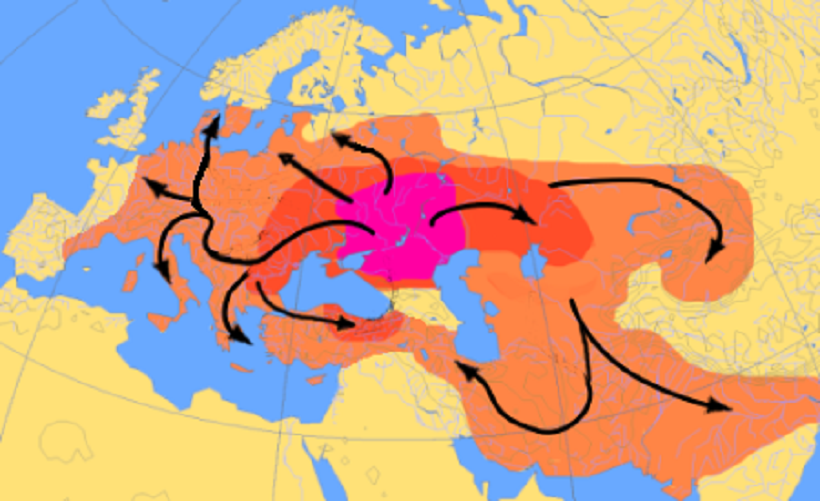

Celtic was part of what's called Indo-European culture. This concept is based mostly

on linguistics, that there are similarities in languages from Calcutta to Derry that

clearly point to a common origin, hence India-Europe. Given that a common culture is the

fundamental evidence, determining where it came from will probably always be conjectural.

Two primary theories put forward place the origin somewhere in the middle of this range, one

in Anatolia and the second and most supported to the north of the Black Sea. This latter

theory is called the Kurgan hypothesis, named after the burial mounds used by a culture

that began about 5,000 to 6,000 years ago. I'm very interested in the concept of

Indo-European, but I'm not an expert on it in any way. I'm aware that in India it's

fashionable to believe that the common origin was in India. This is partly in resistance

to the origin of European scholarship on the subject, which began in the late 19th century.

This is where the concept of Aryan came from, and Christian theology played into it, and a

European nationalism and sense of superiority.

Kurgan hypothesis

In terms of genetics, there are competing theories of the path that R1b took to

come to Europe, but I think there's a clear connection between R1b and Indo-European,

certainly in Europe. One theory is that R1b came through the Middle East, maybe up to the

Caspian Sea, and then spreading from there, finding most impact in western Europe. The

other theory is that all of humankind tended to migrate initially eastward out of Africa

because of the last Ice Age, and the predecessors of the R-haplogroup were actually in

northern India. The peoples who were in Europe before about 15,000 years ago were not R1b.

Regardless of the two theories, R1b went north of the Black Sea like Indo-European culture.

To me the question of the precise location origin of Indo-European culture is when

it happened. If it was 4,000 to 6,000 years ago, then the Kurgan hypothesis is probably

accurate. If it was earlier, especially much earlier, it could very well have originated

in India or somewhere between India and the Black Sea.

Regardless of where Indo-European culture began, where it went is quite obvious. And

though there seems to be a connection to the R1b haplogroup, and R1a, the spreading of

culture isn't always connected to genetics. The pattern I see in the history of

Indo-European culture is one of a ruling class. Indo-European culture moved through a

vast area, and all of it had been already populated by a variety of peoples. They were

farmers and pastoralists, and so also were the Indo-Europeans. I tend to think this spread

wasn't like the Romans conquering Gaul for example, but more peaceful, because it was so

early in the formation of civilizations and kingdoms. That said, the development of

bronze and iron technology, and horseriding, are known to have been fundamentally

connected to the Indo-Europeans. So, regardless of how the spread of the culture played

out, it was a conquering of the native peoples in at least a cultural sense.

Getting back to our ancestors and the European theater of the Indo-Europeans, the Celts

were one (or a few) of the identifiable cultures that developed from the common origin.

Another is Germanic. The Greeks were Indo-European and were the first major empire of

Europe. And then later came the Romans. The Greek theater of activity was to the east,

as western Europe at that time was a patchwork of a variety of Indo-European cultures.

It seems to me that what distinguishes Germanic culture from Celtic is the former

learned (maybe from the Romans) the value of uniting various tribes into a more powerful

entity. Celts were capable of growing larger kingdoms, as evidenced by Gaul, but I think

for the most part they ended up being dominated by other powers due to a tendency

to isolation that was integral to their culture. Also consider the colder weather in the

northern and western extents of Britain and Ireland, and the inherent delay in development

arriving there as mentioned previously.

But let's take a step back to where we left off in the timeline of European history that

would spread to Britain. A variety of cultures have been identified from modern France

and Germany to Ukraine via archaeology that are connected to Indo-Europeans and were

precursors to the Celts. By 4,000 years ago they had spread to Britain and Ireland,

including lots of R1b men in my opinion, maybe the majority of our R1b ancestors.

The definition of these cultures is usually based on their style of pottery and how they

buried their dead. The arrival of Celts in Britain is placed at around 3,300 years ago,

pretty much just after Stonehenge was completed, and it didn't take root in Ireland until

another millenium later, a century or two before the Romans came. As elsewhere Indo-European

cultures spread, the Islands had already been farmed and grazed for thousands of years.

Specifically in this case, where terrain was limited, Britain and Ireland had already

been largely deforested. The Celts had the advantage of iron technology, which probably

was held as a source of power by the ruling class and thus spread the culture. The map

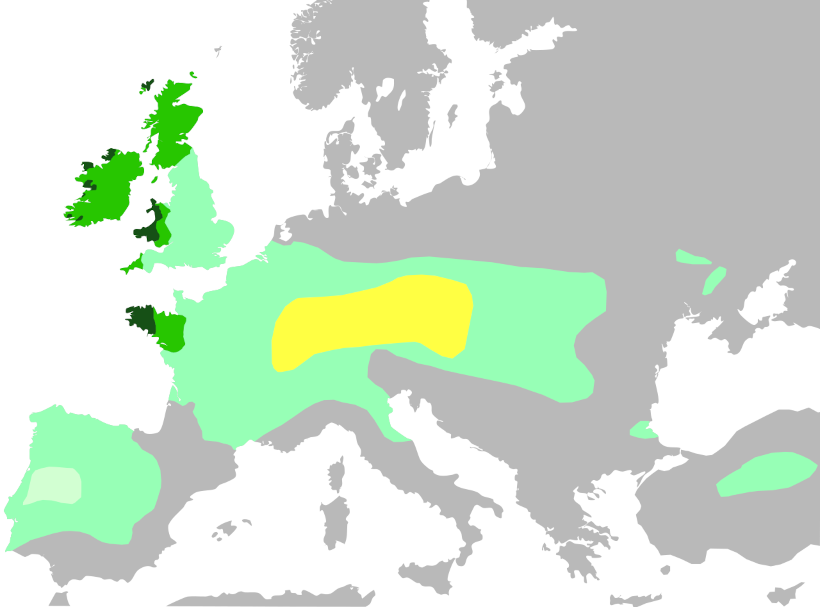

below shows the extent that Celtic culture reached, with the yellow being where it

originated, and the darkest green where Celtic languages are still spoken.

Celtic culture

As human civilization developed, this kind of "invasion" of people and culture became

more complicated, and the idea of an "aboriginal" people became less applicable. But I

tend to believe that our ancestors were more "native" than "invader" and adapted to

cultural changes, because I don't think there tended to be population replacements in

the waves of new peoples and cultures that would continue to come. When the "indigenous"

people became less numerous after an "invasion", I tend to believe this was more due to

being outnumbered and having a shorter lifespan because of their mode of living, than

having been killed by the invaders. It's probable that

men of the R-M269 haplogroup had begun to come to the Islands before formal Celtic

culture did, and the adoption of Celtic language in Britian and Ireland was even more of

an adaptation than a relatively sudden migration of people. Migration of peoples into

Britain probably wasn't the norm over the coming centuries, and I think commerce

became the driving force of events. Commerce creates wealth, and wealth is power, and

power leads to struggles between different chieftains and the peoples they belong to.

The Celtic peoples of Britain and Ireland, which was more of a cultural thing than a

genetic one, formed into tribal territories. The most valuable land was in the south of

what would become England, which was the best farmland due to its warmer climate.

Farther north and in Ireland, the tribes weren't completely isolated, but much moreso. In the south

there was much interaction with the mainland, and this was affected more and more by the

larger developments that came from the Mediterranean.

The Romans

I had thought to make an entirely separate document about the Roman Empire, as there's

so much that can be written about it, and I believe we had Roman ancestors who came to

Britain. But my objective is to keep on the track of British history, so I'm limiting

the Romans to one section here. The origin of Rome fell into the mythic past for the

Romans, but the Greeks claim that it began as a colony started by them. The Greeks

were the first to name the British Isles, calling the lands Albion somewhere around

2,600 years ago. This was the beginning of the written history of Britain. Albion was

the root of Alba, the name of the later kingdom from which Scotland arose. The term

Celt was coined by the Greeks. A Greek called Pytheas from what is now Marseilles

France, voyaged to Britain about 2,300 years ago. He got the name Pretani from the

native Celts for themselves, which meant "painted people". From this the Romans later

named the main island Britannia, with the 'p' shifted to a 'b'. They called Ireland

Hibernia, which didn't come from a Celtic origin. The Romans translated Pretani to

Picti, which was applied by them to the Celts in the highlands of Scotland. From picti

comes the word picture which is familiar to us now. By modern artists the Picts are

depicted, as it were, as being painted blue. Apparently some kind of tattoing was

common with all Celts, at least in Britannia, and I expect it wasn't quite that colorful.

Getting back to Rome, archaeology shows that settlement there began about 3,000 years ago.

This began to ramp up in a couple hundred years, and the Roman kingdom was born. The

oldest discovered Roman writing about the kingdom period is about 2,600 years old.

Putting this into context, Britain had aleady been Celtic for almost a millenium. The

Roman republic was formed 2,500 years ago, and lasted almost 500 years. The kingdom

before the republic had a senate, and it selected a king from amongst themselves. The

first change entering the republic period was to eliminate the monarchy and have

elections for a magistracy. This was no democracy of course, as only the senate

voted. Roman power began to expand before the republic period, and gained momentum

during it. This brought them into conflict with Celtic tribes to their north and west

in the mainland. As the republic began, hill-forts became common in Britain and the

mainland. This no doubt was a reaction to the expansion of Roman power. But the Celts

were also growing in power, particularly in Gaul, which is the model of what might've

been with Celtic peoples if Rome had never existed. The kingdoms of Gaul were much larger

than those in Britain and Ireland. But as the Romans continued to expand, they

conquered the Celts of the mainland, leading up to the founding of the Roman empire

about 2,100 years ago.

We're coming up on the common era now, and Rome began to think of the riches that could

be gotten in Britannia. As previously mentioned, southern Britannia was very much

connected to their Celtic brethren in the mainland. Of our two paternal lines which I

have high confidence came from the Romans, their lands about 2,100 years ago were

conquered elsewhere than western Europe. Our J2 Scott line came from Syria, the eastern

end of the Mediterranean, and our E2 Hollis line came from Mauretania, the western end

of the Mediterranean on the African side. They both became Romanized in the coming

century or two before the Romans went to Britain. It wasn't as much of a change in

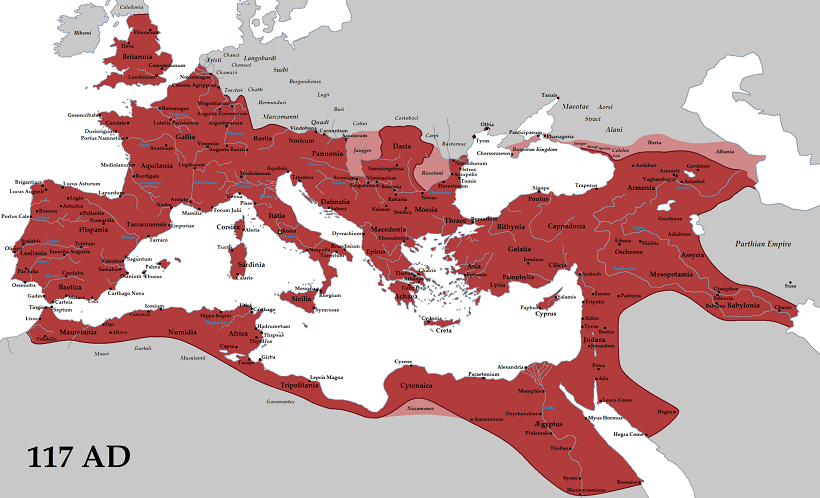

Syria, which had become thoroughly Greek in the preceding centuries. The map below is

looking a bit ahead, but it puts into perspective the breadth the Roman empire reached,

and the far-flung parts that brought a wide variety of people to Britannia.

Roman Empire

Right at the time the Roman republic became an empire, their first invasions of Britannia

were attempted and failed. The Romans had client chieftains in the southern part, who

saw that arrangement as the best way to retain their power. But the people disagreed and

managed to drive out landings that didn't expect resistance. Still, in the year 43 a more

determined invasion was mounted and this planted the Romans in Britannia for the next

350 years and more. They systematically subdued the Britons, the Celtic tribes that had

taken their form over the past millenium. Boudica is a famous heroine of the Britons,

who was killed after a considerable rebellion in the year 60. Hadrian's Wall was built

around the year 120, establishing a demarcation of Roman control. But that said, while

active rebellions in future Wales and Cornwall had been quelled, only the southeastern

part of future England became fully Romanized. If the Romans' years hadn't been numbered,

given enough time their influence would've spread through all these regions and into

Ireland the same way that English influence did in the modern world. The Roman base has

a lot to do with England eventually becoming a world power. See the map below of the

arrangement of Britonnic tribes after Hadrian's Wall was built.

Though a real transition from republic to empire isn't as dramatic as, say, what's

portrayed in Star Wars, when the Roman empire was formed, it was corrupted and was

doomed to fall. It still took over three centuries for things to get so bad that the

Romans formally withdrew from Britannia in the year 410. Several big events in British

history were in motion then, including the introduction of Christianity. Christianity

was foundational to Ireland, maybe more than any country that ever existed. It came

there about the same time that Gaelic culture emerged out of Celtic. Germanic

mercenaries were in Britain before the Romans left, and that set the stage for a

transformational movement into a power vacuum. It wouldn't be the last time. While

only the southeast of England became fully Romanized, the impact of that period remained

all over. Forts were maintained for decades at least. Latin was used in churches and

government north of the Wall, and in Ireland. Latin remained the language of education

in England.

The Roman Wake

The Roman empire had a large impact on most of our ancestors, in that time. Of course

Rome remained the seat of Christendom for all of our ancestors for a thousand years

afterward. It took some of them a few centuries to convert, particularly the Germanic

tribes from around modern Denmark and northward, but though our ancestry came from some

unexpectedly diverse origins, in the wake of the fall of the western Roman empire they

were all now in Christian Europe. The vast majority of our French, German, and Swiss

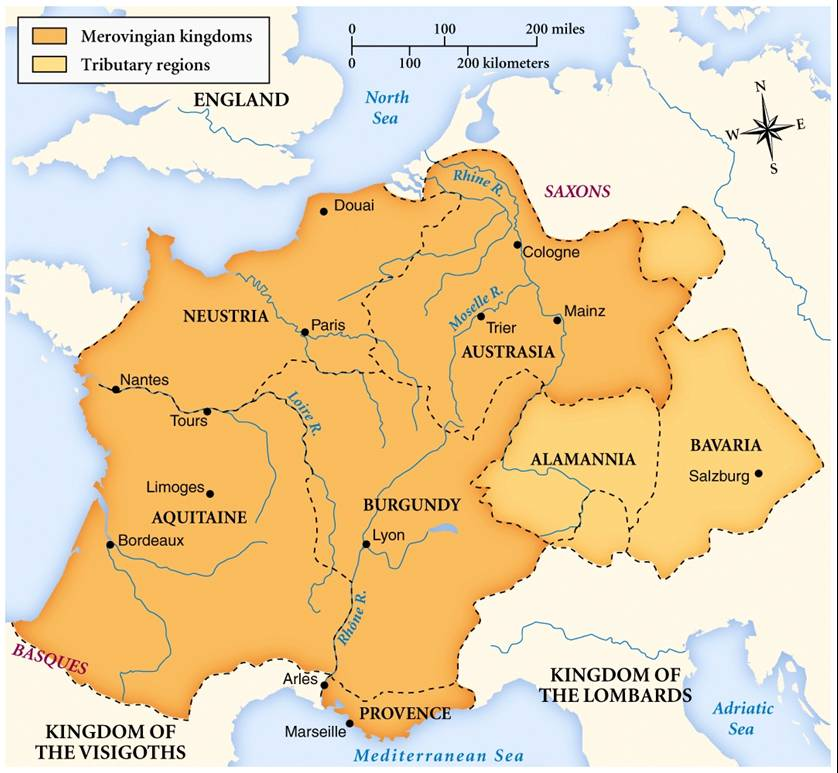

ancestors were the most entangled in it. The Merovingians arose, when Germanic chiefs

took over in central Europe. See the map below. A lot of our ancestors were in the

area marked 'Saxons', particularly those who would move to found England. We will get

to them. A small few were in the Saxon region who would remain there like the others

who were now Franks, until they came to America. A split would occur amongst the

Franks in the coming centuries where the kingdom of Germany was formed (843) and then

it became part of the Holy Roman Empire, unified with Italy and the Vatican. This

arrangement wasn't dissolved until long after our German and Swiss ancestors had

departed for the New World.

Most of our ancestors in what would become England were thoroughly Romanized. Some were

in Ireland and were utterly Gaelic. A few were in Cornwall and

Wales. A few were in the Scottish highlands and were very much like the Irish. Quite

a number were in the area of Hadrian's Wall. These are interesting because some were keen

on being rid of the Romans, while many likely were sympathetic and attempted to maintain

forts and whatnot. But let's get to the power base that would come to create a global empire.

As stated previously, upon the withdrawal of the Roman military from Britannia in the

year 407, British leaders summoned Anglo-Saxon mercenaries to guard against Celtic raids,

particularly by the Picts of highland Scotland. These mercenaries were given territory

for this, I would guess around Norfolk and Suffolk. Probably related to the dissolution of the Roman

empire, conflict between the Britons and the immigrating Anglo-Saxons eruped in 442. This continued

until the year 500, when the rebellion was put down. Now keep in mind that Germanic

peoples hadn't been utterly foreign to Britain previously. There were German soldiers in the Roman legions.

They likely engaged in trade with Britain throughout the Roman age. Germanic peoples

were on the rise and played a large role in the fall of the Roman empire.

The momentum of the Germanic migration into the mainland around Britain is what helped

them to mount an invasion of Britain in a sort of parallel to the Roman invasion centuries

before. But while the Romans were a massive empire with deep resources and sought to

annex the entirety of Britannia, the Angles and Saxons and Jutes and Frisians etc, while

they defeated the British ruling class, they had no empire to add land to and simply

rooted themselves in eastern Britain. The Angles and Saxons were the most powerful, and

their culture was the one now established as the ruling class, at least in the area they

controlled. The Roman legacy remained, I think, and it merged with Anglo-Saxon culture

to form something distinct from the lands they came from. As for what portion of our

English ancestors were invaders and what portion were native, as I've said I believe the

latter group was much larger. Surely the number of Germanic peoples who migrated to

Britain at this time was significant, but I don't think the portion of them that were of

the R1b haplogroup was comparable to those who had already been in Britain before the Romans.

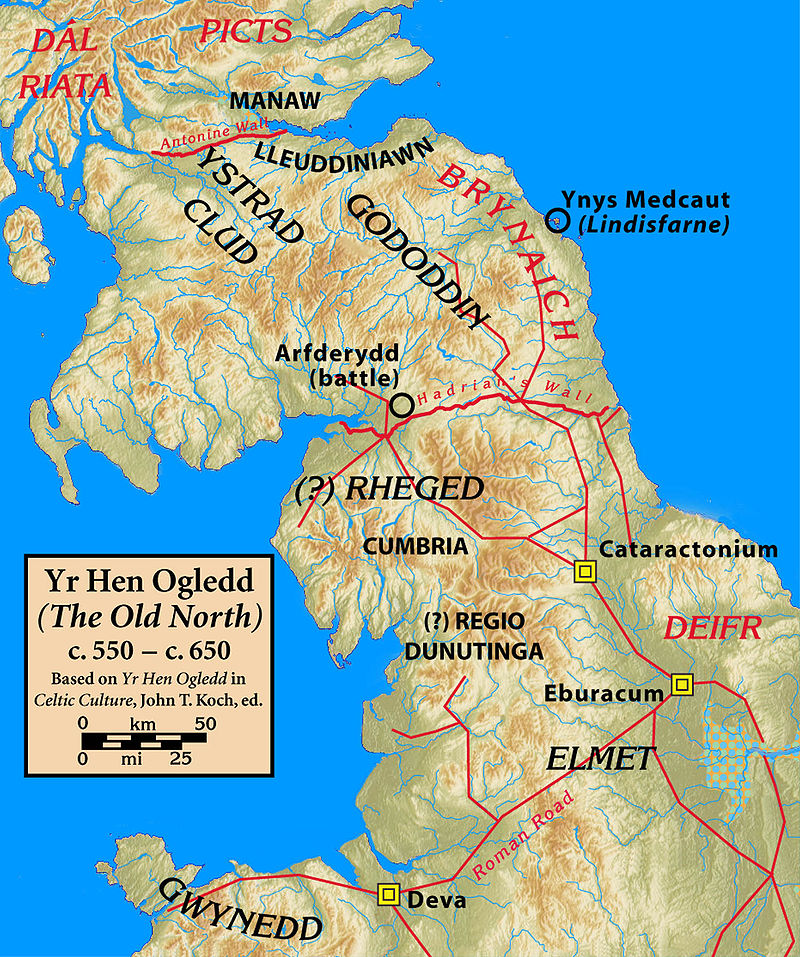

The Old North

As the Angles founded kingdoms in eastern Britain from modern Edinburgh to Birmingham to

Norwich, and the Saxons in southern Britain from Exeter to Bristol to London, in Ireland

and Cornwall and Wales and western Britain up through the highlands, Celtic tribes

remained as they had been when the Romans landed, and they had survived and were as

strong as ever, if modified and affected by changes within. Still, there was no movement

to unite into one nation against the new invaders. But while there was conflict between

Celtic tribes, there was also kinship over large areas. One of these was, before the

Romans came, from what is now northern Wales through Carlile and Glasgow, eastern northern

England and Scotland. Though the Romans impeded the land connection between Wales and

their northern kin, they remained in contact. In Wales they called their kindred tribes

there the Old North, or Hen Ogledd. See

the map below from the year 550. The Angles formed two kingdoms from the east coast,

Bernicia which took its name from the Celtic kingdom Brynaich, and Deira from Deifr.

Three other Celtic kingdoms of the Old North were prominent in the wake of the Roman

withdrawal, including Elmet which was absorbed into Deira and Gododdin which was absorbed

into Bernicia. The land northwest of Rheged became the kingdom of Strathclyde. That and

the also-kin kingdom of Dal Riata in the eastern highlands were fundamental to the

eventual formation of the country of Scotland.

The Danelaw

The England we know today didn't form in a simple process. Hardly. First, several tribes

shaped the country, including Brittonic ones, yet the name and language came from only one,

the Angles. The Germanic tribes that came in had no grand plan to form a country. They

hadn't come from a country. The concept of England took several centuries to develop. Of

course the Angles and Saxons were the most prominent and formed the ruling class. The map

below shows how the two had solidified control of most of what would become England. The

Northumbrian kingdom was probably the most formative of our ancestors, even the Scottish

ones, as you can see that it stretched all the way to Edinburgh (Lothian). While highland

Scotland came from Gaelic culture, the eastern lowlands didn't. Remember that most of the

area of future England had been thoroughly Romanized, except for the western extreme of

Saxon territory and approximately the northern half of Northumbria. It took longer for the

western part to formally merge into England, especially Wales, and even Scotland became

part of the United Kingdom eventually. As I said before, I think the Roman influence is

what set the course for England to be the dominant power of Britain, but the Celtic influence

had a lot to do with the cultural character.

The fact that Norfolk and Suffolk today come from what was called East Angles shows that the

Angles and Saxons were definitely not originally united, as Saxon territory clearly formed a

separation. It was just after this time that the land became Christianized. It was the

Irish who drove the process, and it spread from the north to south. As was the case throughout

Europe, many pre-existing practices were adopted into the religion, and the full transformation

took centuries to complete. There was still no unity called England, but the term English

for the common language came into use by 731. It seems that it was called English and not

Saxonish or something else, because of the Britons. Because they always called the newcomers

Anglo-Saxon, with Anglo- always before Saxon, the term was shortened to just Anglish, or

English.

Though the Anglo-Saxon immigrants defined the language and eventual title of a country that

would form, it had yet to happen when a new wave of immigrants came and had a similar affect

to what the Anglo-Saxons had done. Vikings were Germanic immigrants coming from Scandinavia,

just north from where the Anglo-Saxons did. They probably came for similar reasons: increasing population and pressure from

an inhospitable climate compared to the south. The Vikings have a reputation for having been

more aggressive, pillaging and plundering. But they also settled. In the same migration

period, they settled Iceland, were the foundation of Russia, took over Normandy in France, and

even attempted to settle North America. It was in this period that our Scandinavian

ancestors settled in England and Scotland. They founded Dublin in Ireland and the major towns

around the southern coast, though I don't think we have any Scandinavian lines from Ireland.

The Vikings were not Christian, which probably is the foundation of their barbaric reputation

from the English perspective.

Britain in 878 AD

The map above shows the impact the Vikings had by the year 878. They conquered kingdoms of

the Angles primarily, leaving only a portion of Northumbria. What would become English was

basically the Saxon kingdom if Wessex in the south. The non-Christian Danes ruled a vast

area that was called the Danelaw, I guess by Wessex. They came mostly from Denmark.

Cornwall had now been incorporated by the Saxons. Wales remained as its own entity, as did

Strathclyde in the Old North. I'm sure that some of these Vikings were our ancestors, but I'm

not sure if most of ours came from the Danelaw or the Normans. As happened elsewhere with

the Vikings, they eventually merged into their new country. They became Christians and were

part of the formal unification of England in 927. They had an impact on the English language,

which isn't as noticeable as what would occur later because Old Norse was also Germanic. So,

though the Anglo-Saxons had been there centuries before, the Danes weren't that foreign and

were simply another warring Germanic tribe that made up what would become England.

The Norman Invasion

The now-established country of England existed for just over a century before another Germanic

invasion occurred. This one spoke French, because the Vikings who went to Normandy (which

was named after them, North-men), became French like the Danes had become English. In the

year 1066 the King of England died, and it triggered a succession crisis. William of Normandy

saw the opportunity of taking the kingship himself, and he led a force across the Channel that achieved it. The

bringing of the French language probably in the end had the biggest effect. Our ancestors who

have French names obfuscate whether they came to England with the Normans or if they simply

adopted Norman names because the French language held sway in the nobility for many centuries.

Today's English language is a mixture of Germanic and Latin elements that makes every rule

have an exception. The Norman invasion was genetically confusing as well, as the Norman

ruling class was probably the Viking I-M253 haplogroup, but Normandy is predominantly R1b.

The Anglo-Saxons likely had a similar genetic makeup. My presumption, as I've stated before,

is that most of our R1bs came to Britain even before the Celts did, let alone the Germanic

tribes.

The Norman conquest, as you might have deduced, I see as a great disruption in English history.

That really is only due to the French language, and I see English surviving and eventually

reviving. The language is still called English and is more colored by French than to have

become a Germanic-colored Latin language. But the England we know really was established by

William of Normandy, as we know it by kings named Henry, which is a French name. A section in

this document on the Normans maybe should be larger than this one is, but as it stands, just

realize that Norman England is inherent to the story going forward.

Scotland

Let's go back now to the Old North and Strathclyde and Dal Riata, the former with a Britonnic

history that came into conflict with the Romans and survived, the latter a Celtic kingdom

founded by Irish immigrants. The formation of what became Scotland originated in the north.

The Picts were the most isolated group, even by Irish standards. The first step in this

formation was the merging of the Picts and Dal Riata. The Picts became Christians and also

began speaking Gaelic. Strathclyde then merged in, and in the 9th century the concept of the

king of Alba came to be, and the term Scotia, eventually Scotland. We have ancestors from all

four corners of Scotland, with more as you go through them counter-clockwise from the highlands.

This is no coincidence, as the southeast of Scotland is a region that was fought over between

Scotland and England for centuries before North America was colonized. Life was usually

difficult there, and that drove our ancestors to leave, often first for the

Irish plantations, and eventually to America.

The arising of Scotland occurred when the southeast part had been thoroughly Anglicized. Our

border region ancestors were never Gaelic speakers. Most of them had been Brittonic Celtic

tribes when the Romans came, and they spoke a precursor language to Gaelic. But what defined

them most by the year 1000 was the Anglish kingdom of Northumbria. As was covered before,

during the Danelaw Northumbria remained Anglish. What's called the Scots language is now

spoken in the lowlands, which reflects the influence of Gaelic on the English language in the

period where it became part of Scotland, not the earlier Brittonic language. The

instability of the border region would continue with the coming Protestant reformation.

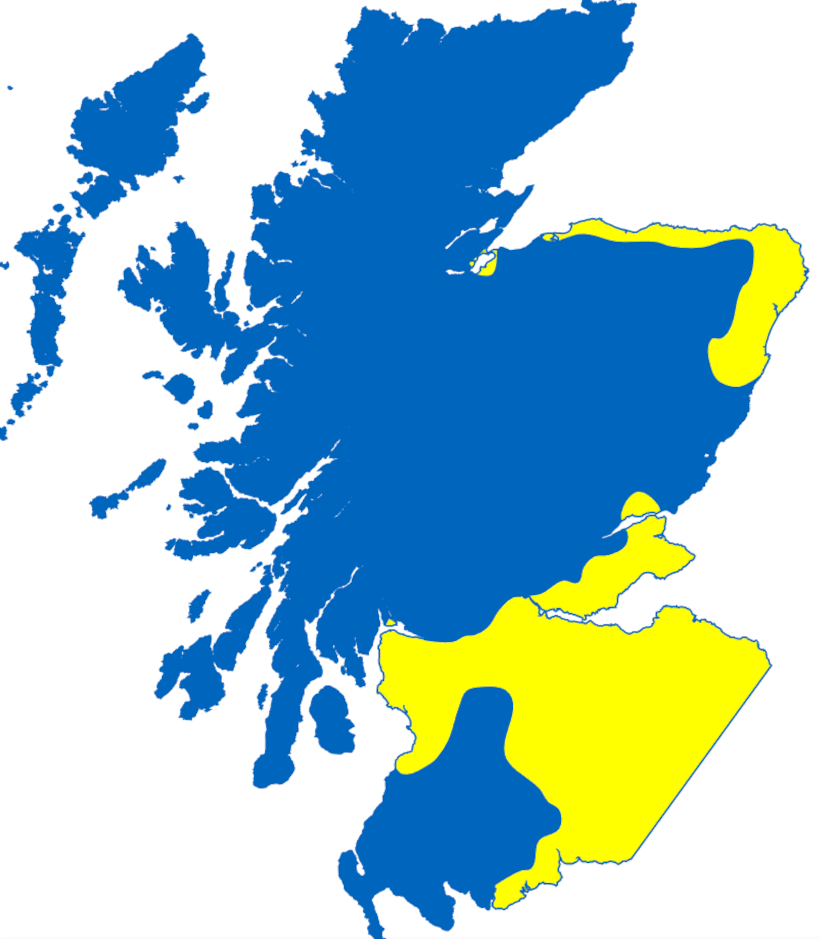

Languages of Scotland - blue=Gaelic, yellow=Scots

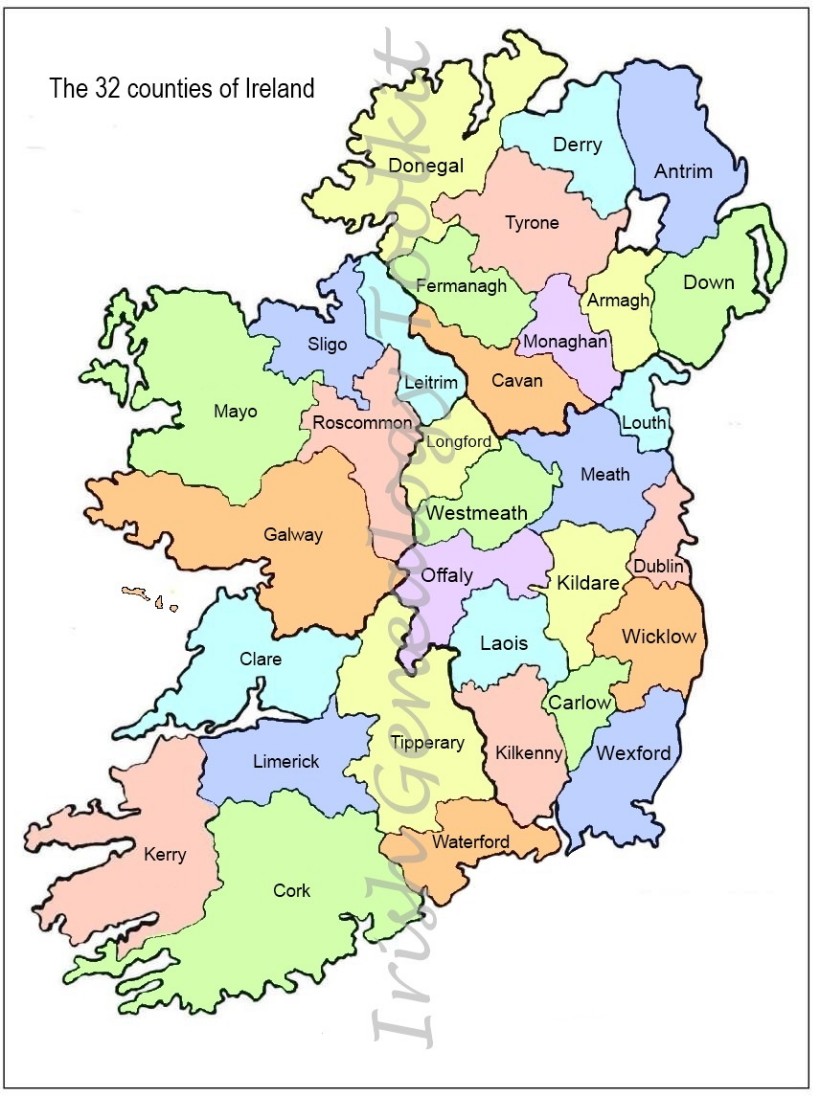

Ireland

The history of Ireland is fairly murky. The name Ireland was only formalized in the 20th

century. The origin of the name is uncertain, coming from a Celtic root or maybe even from

the name Hibernia that the Romans called it. As I stated before, my understanding is that

what we call Ireland was formed when it became Christianized in the 5th century. Of course

it had a history before that, which was defined by competing Celtic tribes. With the rise

of Christianity the territorial rivalries continued, now forming into kingdoms. At the

same time the Vikings began raiding and settling Britain and central Europe, they did the

same along the eastern and southern coasts of Ireland. Vikings came to rule Ireland similarly

to the Danelaw in England, and Normandy in France. When the Normans invaded England, unlike

the Romans, they also took control of most of Ireland, the groundwork having been laid by

their Scandinavian kin. And as happened everywhere the Vikings went, they enthusiastically

merged into Gaelic culture. Surely more could be written about Irish history, but though we

had several Catholic Irish ancestors, I know next to nothing about their deep history. Only

our McAtee line connects clearly to one of the Irish kingdoms, that of Airgialla, also called

Oriel. That would be worth learning more about.

Protestant Reformation

The Christian religion had a great impact on our ancestors from the time it was adopted in

the wake of Roman Britain, to the present. Certainly the belief systems that preceded it

were foundational, but I don't see obvious religious impacts on the historical trajectory

before Christianity. Probably before writing it just can't be known. There is archaeolgical

evidence of burial practices, and human sacrifice, which were part of the evolution to our

present sensibilities. The greatest impact on our ancestors that I can see before Christianity

was the agricultural revolution. Catholicism from the start was a unifying force, as far as I

can tell, forging Ireland as we know it, and spreading through all of Britain. It's likely that

the conversion process wasn't smooth at all, but in the end Christianity really established

Europe as a concept. Religion became integrated in the power structure of European kingdoms,

which became the source of great strife that is the narrative of the rest of this document, and

eventually drove emigration to America.

I'm not an expert on Christianity, nor the Protestant reformation, but I can see its impact.

There's a proverb that says "power corrupts". It's a proverb because it's true, even though

people will continually fail to realize it until it's too late, because power is seductive and

humans will insist on believing that they know better than everyone who's come before them,

that they won't be corrupted. Either that, or they just rationalize the corruption into

something beneficial. The concept of separation of church and state, as we call it in America,

is all about the corruption of power. The spiritual power of religion is corrupted into a

material power when it's integrated into the state. The state, as we've learned in America,

can already be corrupted by the power of wealth, without integrating it with religion. The

corruption of wealth consumes democracy and generates poverty and oppresses the poor. The

corruption of religion consumes democracy and oppresses those not of the chosen sect.

I'll take a step off my soapbox here, just one, as we go back to 16th century Europe. I'm not

going to attempt to understand what the Protestants were protesting, as I take no side, except

against oppression. We had Catholic ancestors, and of course the vast majority became

Protestant, and different sects slaughtered each other and oppressed each other over it. You

might notice that I greatly rue all of it. We have lines that in the past were at each others'

throats at times, yet eventually were joined together. To me it shows what an absurd tragedy

the past conflicts were. I see no value at all in any of it, unless they actually stopped

oppression without replacing it with only a different oppression.

But taking the other foot off, and getting back to what happened, Martin Luther in future

Germany catalyzed what would be the Reformation. Conflict there in the process led to the

immigration of all our German and French ancestors in the 18th century before the American

Revolution. But this narrative will return to focus on Protestantism in Britain. As you

probably are aware, in 1527 Henry VIII asked the Vatican to have his marriage annulled. When

the Pope refused, Henry decided to separate the Church of England from the papacy, which

established Protestantism in Britain. Though Luther's ideas had been recently percolating,

this was a completely poltical move and began a bloody power struggle that greatly affected

all of our British and Irish ancestors for centuries to come. I truly don't know how things

would've played out if not for Henry VIII. It seems unlikely that all of Britain would've

remained Catholic, but I think it's possible. Henry's move seems to me to have ended Norman

England and guaranteed future strife with Ireland.

Henry VIII

We'll come back to England, as the religious struggle there was fundamental to coming events,

but let's now look at Scotland. As was stated before, Gaelic Ireland was rooted in

Catholicism, maybe more than any other people. I don't know what all the dynamics of the

development of Presbyterianism were. I do see it as less corrupted than the Church of England,

coming from maybe a more spiritual origin. But this could only be due to Presbyterians not

having the opportunity to merge with the state, like the Church of England. One thing I do

rue very much about Anglicanism is its correlation with the practice of slavery. I'll never

accept any religious excuse for the very worst form of oppression that humankind has ever

conceived. Presbyterians didn't approve of slavery, but I do believe there were exceptions

in America. Ireland had a pull on Gaelic Scotland, and I'm not sure to what extent or speed

it converted to Presbyterianism. But the lowlands followed England in the Reformation.

Given that this happened after Henry VIII's gambit, political influence on the development of

Presbyterianism can't be denied. Regardless, Protestantism was planted in Scotland, and for

the moment, all of Ireland was Catholic.

It may be impossible to understand all the dynamics behind the coming turmoil. What I'll do

going forward is focus on how England was ruled without digging too deep. Henry VIII's first marriage

produced one surviving child, a daughter named Mary. England had only had one queen and Henry

was determined to have a son. When he succeeded in annulling his marriage to Catherine of

Aragon, it made Mary illegitimate and he wed Anne Boleyn. The only surviving child of that

marriage was a daughter named Elizabeth. Henry had Anne executed and Elizabeth declared

illegitimate, then he wed Jane Seymour who gave birth to a son named Edward. Jane died from

that birth, and Henry died in 1547. Scotland declared war twice on England in Henry's time,

and both times Scotland was defeated. Henry's son became Edward VI, and was nine years old

when Henry died. Mechanations surrounding Edward converted England to Protestantism, and he

died before he turned 16. With no other sons of Henry, his first daughter became Queen Mary

I. Mary remained Catholic and was determined to reverse the English Reformation. This led

to violence against Protestants, and when Mary died five years later it was celebrated.

Elizabeth I

Henry VIII's second daughter then became queen Elizabeth I. She re-established the Church of

England, and attempted to maintain peace between Catholics and Protestants. She helped to

decrease the power of the nobility and replace it with a common law parliament. Scotland

became Protestant at this time. Elizabeth's reign is seen as a golden age, where a sense of

British nationality arose and England grew more powerful. Shakespeare was in his prime, and

it was an age of exploration and desire for expansion. Columbus had discovered the New World

almost a century earlier. The Spanish were even more powerful than the English, and while they were colonizing

South America, they attempted to invade England in 1588. The latter failed, allowing England

to continue to ascend. Elizabeth died in 1603 with no heir, and King James VI of Scotland was

also named king of England. Jamestown was founded in 1607, named after him. He made peace

with Spain and the relative prosperity of Elizabeth's reign continued for another few decades.

James I of England

Colonization and Plantation

Recall that Ireland had been conquered by the Normans in the 12th century. By the 16th

century, the Norman-Irish had thoroughly merged with the native aristocracy, and were no

longer amenable to England. As England began to send voyages to the New World, and engaged

in piracy on Spanish ships carrying treasures looted from the empires of central and south

America, the English saw the Irish as a savage people like the Native Americans, and sought

to convert and pacify them. The English used resistance as an excuse to confiscate land,

which was turned into plantations that the aristocracy owned and the Irish worked to

produce crops. The process began in 1556 of Elizabeth's reign, from the remaining Norman

base of Dublin. The plantations of Ulster began in the eastern part in 1571. The Munster

plantation was established in 1583, which was England's first colony, not only controlled

but settled by English people.

Munster was the model the English intended to apply in North America, initially as a base

for piracy of the Spanish. The first attempt in 1584 was called Roanoke, still during

Elizabeth's reign, along the coast of modern North Carolina. The early attempts at

settlement were ill-prepared, and the Roanoke settlers had disappeared by 1590. The story

is a curious one if you wish to research it, but I won't go down that rabbit hole here.

As we know, Jamestown in Virginia was able to survive after a rough start to say the least.

The early Jamestown settlers have been characterized as effete treasure seekers, but

certainly when the population began to grow, the majority were indentured servants. As

was the model in Munster, the aristocracy owned the land and the people they brought over

to work it took on a debt in the hope of improving their lot. The practice remained

common into the 18th century, and probably the majority of our ancestors were indents.

Like in Australia, England "transported" people they considered troublemakers to America

rather than keep them imprisoned at home, and they served indent terms. Early in the

history of Virginia the first Africans were brought entirely against their will, and

outright slavery eventually supplanted the indentured servant model. The concept of

capitalism is based on the value of human labor, and slavery obviously returned the

maximum profit. The Plymouth colony was established in future Massachusetts in 1620,

which we do have a connection to, but tiny compared to our history in Virginia. Maryland

was established in 1632 by the Calverts as a haven for Catholics, but without shunning

Protestants. In fact, the population of Maryland was mostly Protestant from the beginning.

Of interest to the British, and our ancestors, was the Dutch settling of land between

Plymouth and Virginia beginning in 1615. By 1660 the Dutch had settled all of modern New

Jersey, northern Delaware, Philadelphia and surrounding areas of future Pennsylvania, the

southeastern corner of New York (especially Manhattan), and western Massachusetts. They

called this area New Netherlands, and they called the town on the southern tip of Manhattan

New Amsterdam. In 1638 the Swedish established what they called New Sweden on the Delaware

river. Philadelphia would later be created by the English on the western side, and

Wilmington Delaware is at the northern tip of what would become that state. The area of

New Sweden was within territory claimed by the Dutch, and the Dutch ended up taking

possession of the Swedish settlements in 1655.

English Civil War

Back in 1625 England, King James died and his son became Charles I, king of England,

Scotland, and Ireland. Charles wed a French Catholic princess, I believe in the interest of

having peace between Catholics and Protestants, but it led only to worse antagonism. At

the same time, the Thirty Years War raged in mainland Europe, at least largely on similar

religious grounds. This was a time of rise in authority of the parliament and Common Law,

and Charles struggled to have his will as his predecessors had, when parliament acted to

restrain him. The prosperity and relative peace established in Elizabeth's reign and

through James's, ended in a big way in 1642 as the conflict between loyalists to the divine

right of the Crown and the Parliamentarians erupted in Civil War. Charles was executed in

1649, and Oliver Cromwell led the Parliamentary forces in victories in Scotland and Ireland.

Cromwell was effectively the leader of England until he died in 1658. Charles II became

king and the monarchy was restored in 1660. London was hit by a plague in 1665, and the

Great Fire in 1666.

Oliver Cromwell

A man named George Calvert was emblematic of the complexities of religious life in England.

Though he was raised with considerable Catholic influence, he lived as a Protestant through

a long career in the English parliament. He rose in power until he became the first Lord

Baltimore, taking possession of land in Ireland by that name. When he retired from the

English political scene he converted to Catholicism and invested in settlements in the New

World. This led to the foundation of the colony of Maryland, which he didn't live to see.

His sons completed the work, with Leonard Calvert becoming the second Lord Baltimore, and

Charles Calvert the third. Maryland was intended to be a haven for Catholics in America,

and yet attempted to be tolerant of Protestants. As stated before, Catholics were the

minority population of Maryland from the beginning. John Hollis was an early Protestant

settler of St Mary's, the first capitol of Maryland. He was either one of just a few

Protestants there, or more likely they were more common before the English Civil Wars

began. That conflict spilled over into Maryland, being the only colony with Catholics at

the time, in 1644. John Hollis participated in what was called Ingle's Rebellion,

betraying what I see as genuine toleration of Protestants by the Calverts, attempting to

wrest control of Maryland from Catholics. They failed, and John moved across the Potomac

to Virginia rather than swear fealty. Eventually the continual resistance against

Catholic rule in Maryland led to the Calverts themselves converting to Protestantism in

order to continue governing the colony.

English Ascendancy

Charles II's reign began with a much less powerful monarchy in the wake of the English

Civil War. Charles died in 1685 and his brother James was his heir, and he was Catholic.

When he was named King James II of England and VII of Scotland, he was then forcibly

replaced by William of Orange, husband of Charles's daughter Mary, who was Protestant.

Rebellions in Ireland and Scotland then occurred through 1745, attempting to restore James,

and after he died, his heir also named James. I've stated in the Scott document that they

were part of these Jacobite rebellions, but they were Presbyterian and would seem to have

been on the side of defending Protestants against the rebelling Catholics. I've found the

machinations that occurred impossibly confusing. Scots are often

presented as a unified force, but the truth is the highlands remained Catholic for a

long time, while the lowlands largely converted to Protestantism just after the English

did. We had a few highland Scottish ancestors who may have been Catholic, but the most

part were from the southern part of the country and I presume were predominantly

Presbyterian. The Scotts certainly were. But even so, the Presbyterians were at odds

with the Anglicans, and our immigrant Andrew, even if he was on the Protestant side, he

could've been targeted for transport to America by the English.

Charles II

Back to the developing colonies, in 1609 the Virginia colony claimed lands from modern

Pennsylvania south to below the modern southern border of Tennessee, and west to the

Mississippi River. This area covered 16 modern states. With the Spanish having claimed

Florida a century earlier, England was concerned with them expanding northward. In 1663

King Charles II granted a charter to form the colony of Carolina, or Carolana, named after

him. The original border with what remained of Virginia was a bit south of where it is

now, but was moved to the final latitude in 1665. The 1663 southern latitude of Carolina

was around modern Natchez Mississippi, and was moved more aggressively south in 1665 to

below the southern extent of Louisiana. All lands west to the Mississippi River continued

to be claimed by Carolina. Charles Town, modern Charleston South Carolina, was also

named after Charles. Settlement in the southern part was limited to the Charleston area,

and in the northern part along the coast closer to Virginia. The distance between the

populations and the difference in terrain and lifestyle, resulted in the two being

separated, eventually into the North and South Carolina colonies in 1712. Georgia was

formed from South Carolina in a similar manner to how the Carolina province had been

formed, claiming all of the future states of Mississippi and Alabama. But only the

northeast corner of Georgia was settled for a long time, mostly because of Cherokee and

Creek populations. The pressure of American settlers took until the early 19th century to

fully push them all onto the Trail of Tears to Oklahoma.

Given the broad claims of Virginia, there was friction with Maryland over what territories

were part of it or Virginia. Many of the participants in Ingle's Rebellion lived

around the Potomac and were aggrieved by their properties being given to Catholic Maryland.

Farther north, war between England and the Dutch resulted in New Netherlands being taken

over by the English in 1664. In the brief time that James II was king, the colony of New

York was named after him, as he was also the Duke of York. That's how New Amsterdam

became New York City. The colony of Delaware was organized in 1701, and New Jersey in

1702. As that process was unfolding, William Penn was granted a charter in 1681 from which

the colony of Pennsylvania was formed. It wasn't until 1767 that the final southern

border was established after Maryland had similar friction on that side. There was a

competition with New York and Connecticut over the northern border, and the southwest

corner wasn't ceded by Virginia until 1780. Now the Atlantic seaboard from Maine to

Georgia was British, and the course was set for what would become the United States.

This happened even as the British Empire expanded around the world. In Ulster the import

of so many Protestants from Scotland changed the character of the land such that it was

aligned with England and remained part of the United Kingdom as Northern Ireland when the

rest of Ireland became the Republic of Ireland in 1922.

This is a tale of the history of Britain and Ireland from the perspective of our

ancestors, so it ends with the American Revolution. I might attempt to write that up

as its own document, so it won't be here. What I think is most important to address

briefly is that it wasn't as simple a thing as we see it now. We definitely have

ancestors who were loyal to the Crown and wanted to remain British. Many loyalists,

known as Tories, fled to Canada. But not all of them. Many Tories were hung or killed

in even more barbaric ways. And the Tories weren't gentle with Patriots, either. As

with the later Civil War, choosing sides wasn't always easy. It seems pretty obvious

that anyone who didn't want a revolution and yet remained in America, kept quiet about it

and adapted. Therefore it may be impossible to know. What matters is they remained and

became American. But I do wonder if the antagonism toward secularism in this country

was rooted in them. Loyalists tended to be wealthy and owned slaves, and dynastic wealth

still has strong connections to the origins of the English colonies.

last edited 1 Dec 2022